Real thought leaders aren’t perfect know-it-alls (+ tips)

I’ve spent about 39 years hurtling around the sun on this little blue space rock. In that time, I’ve developed a few obsessions. For instance, as a downright fanatical movie nerd, I love spending hours reading obscure movie trivia facts. (Did you know it was Tommy Lee Jones’ idea to paint his entire body gold in Oliver Stone’s JFK?)

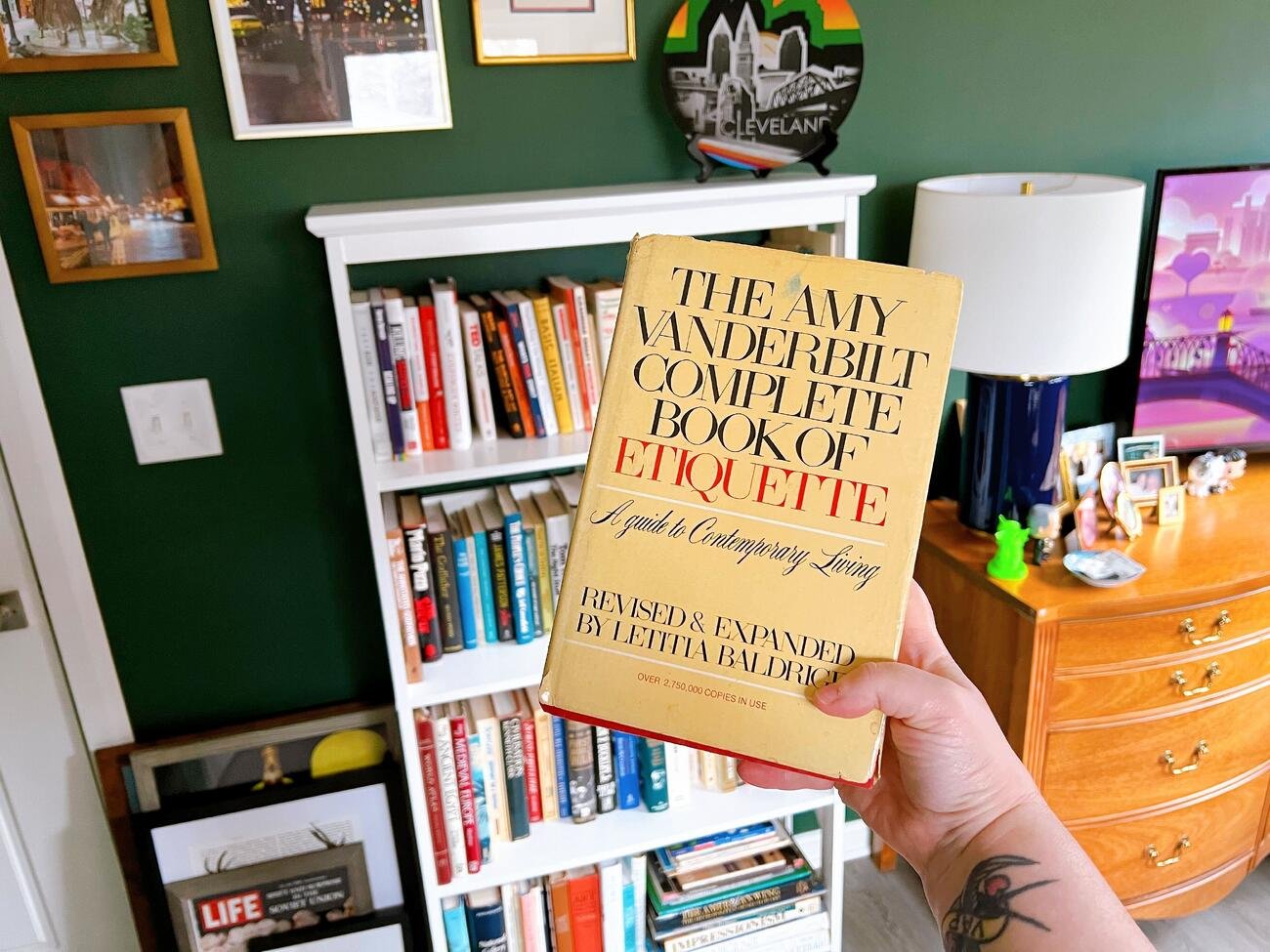

I also cannot count how many hours I’ve dedicated to the research of old etiquette rules and societal expectations. This is probably why I consider this …

… to be one of my most prized possessions.

Meet The Amy Vanderbilt Complete Book of Etiquette: a Guide to Contemporary Living, now available in a new edition. This delightful treasure of mine was first published in 1952 and then was lovingly updated in 1978, which is the copy I own.

With chapters like “An Audience with the Pope,” “Men and Women as Colleagues in the Office,” and “Household Management in a Serventless Society,” it’s packed from cover to cover with indispensable gems like:

“A woman traveling on business alone: Traveling alone is just as lonely for a woman as it is for a man, only more so, because a woman is more limited in what she can do by herself in the evening.”

“After dinner don’ts – making everyone dance: The hyperthyroid hostess who rushes her guests into dancing the minute they leave the dinner table should take lessons in self-control. Not everyone is an aspiring Fred Astaire or Ginger Rogers. (However, one of the best parties I ever attended had two professional ballroom dancers come in after dinner.)”

“How to eat various foods (at the table with company present), grapes: Grapes are cut with grape shears or with scissors in a cluster from large bunches in a passed bowl. You eat one grape at a time, and the tiny pits are deposited in your cupped hand and then placed on the plate. It’s pretentious to peel your grapes – leave that for gourmet recipes!”

Basically, it’s a detailed, 841-page dissertation on why I would have been labeled an outcast by all polite society back in the Mad Men era.

Although, I’m not sure I consider that to be a bad thing. Can you imagine having to adhere to so many rules? One slight misstep – peeling a grape at the dinner table (gasp!) – can send tongues wagging about lack of breeding behind your back.

Yes, many of these rules are relics of the past, but they do speak to something that’s still very much alive today, whether we want to accept it or not.

When it comes to thought leadership and creating content, we talk about the virtues of being ourselves and authentically human; in fact, we can’t seem to shut up about it, myself included. But for all of our authenticity posturing, there are unspoken rules many of us avoid breaking at all costs because we are deathly afraid of eroding our credibility and looking stupid.

I don’t want to look stupid either

I can’t even begin to count the number of times I (as the supposed “expert”) have been asked questions publicly that made my stomach drop because … well, I wasn’t really sure how to answer immediately, OR I knew the answer and thought they wouldn’t like it. And I would wager $1,000 of someone else’s money that, no matter how advanced and established you are in your own career, you likely can relate to what I’m saying.

Moments like that totally suck. When you put yourself out there as a professional “know-it-all” in your industry, the last thing you want is for someone to come along and make you look like you don’t actually know what you’re talking about.

So, what do a meaningful number of us do?

Well, either consciously or unconsciously, we pass everything we say, write, film or create through a mental reputation test.

“Will this make us look bad?”

“Are we damaging our credibility by sharing this?”

“What if we turn some people off by being too honest?”

On the surface, challenging questions like this seem like a good thing. In fact, I’d argue that it’s wholly irresponsible to throw caution entirely to the wind when it comes to how you safeguard your reputation in the content you publish.

But there is a Grand Canyon-sized difference between a healthy system of checks and balances with your content, and censoring yourself artificially out of fear. When you lean more toward the latter, that’s how you fall into the trap of believing to be taken seriously in your field as an expert:

You can’t really, truly fail publicly. All broadcasted failures must have the right spin, contextualized historically as really being a long-term success.

You must always be consistent in your ideas; changing your mind a lot and disagreeing with yourself can seem flaky.

And, last but not least, you have to at least seem like you know everything; a genuine “I don’t know” response will undermine your authority, or at the very least make you seem unprepared.

Big oof – how can any of us ever live up to these expectations? The answer is you can’t, and here’s why:

You don’t know everything.

Sometimes “I don’t know” is the honest answer.

Sometimes an honest answer isn’t going to be the likable answer.

We all fail. Over and over again. And, most of the time, it’s not neat and tidy.

As you learn new things, your perspectives will shift. You may find yourself no longer believing what you once believed to be true.

As experts, we don’t have to know everything

Yet, we continue to pretend we do. Sometimes, the reason is fear. (We’ll come back to this again later.)

But other times, whether we like to admit it or not, it’s just about plain ol’ ego. And nowhere in the thought leadership game is this more clear than in the realm of predictions:

“Smart people love to make smart-sounding predictions, no matter how wrong they turn out to be.”

This is a quote from Think Like a Freak by Stephen J. Dubner and Steven D. Levitt (of Freaknomics fame). And one of my favorite chapters in it (the one featuring the above quote, as luck would have it) is how the three hardest words for anyone to utter out loud are not “I love you” or “The Godfather sucks,” but rather:

“I don’t know.”

And yet we well-meaning, audience-seeking experts can’t seem to admit (at least publicly) that we don’t know everything, even though it’s impossible for us to do so.

I wish we were all a little more like this guy, whom I discovered thanks to Stephen and Steven:

Oh my gosh, I love this commercial from Ally Bank. I love this so much, because it’s the perfect (albeit hyperbolic) example of how to be confident in, well, not knowing something and actually bolstering your expertise by confidently not knowing something.

As experts in our given fields, we don’t like to admit there are boundaries to our knowledge or that we can’t really predict the future. The reasons why these limits exist vary, of course:

If someone is asking us a direct question, we don’t want to let them down by saying we don’t know something. Or, more truthfully, we don’t want to be caught with our pants down.

Reward systems are baked in for those who make predictions, specifically, that turn out to be correct. If you gamble by making an audacious prediction publicly and are proven right, you’ll elevate your reputation and (potentially) be called upon for more lucrative ($$$) opportunities.

We are so wedded to our beliefs, we don’t leave room for the fact that we might be wrong; we consciously or nonconciously decide we don’t need to learn anything else.

We fall into the trap of declaring something as fact when it’s really based on pocketed, anecdotal evidence and gut feelings; too often, we don’t put our ideas to the test with experimentation or data once we believe something might be true. Instead, it becomes true because we want it to be true.

We don’t even realize the limits exist, because we overestimate our knowledge and our abilities to predict outcomes.

One of my favorite examples of this (which I discovered in Think Like a Freak) comes from an irony-laden titled article, “Why Most Economists Predictions Are Wrong” by economist Paul Krugman.

One of his primary arguments was that, often economists “overestimate the impact of future technologies” on the economy. Then, he goes onto say:

“The growth of the Internet will slow drastically, as the flaw in ‘Metcalfe’s law’ – which states that the number of potential connections in a network is proportional to the square of the number of participants – becomes apparent: most people have nothing to say to each other! By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.”

Oops.

But this is the kind of behavior we engage in all the time, in every part of our lives.

For instance, 73% of U.S. drivers rate their driving skills as “better than average.” The data, however, doesn’t support these self-assessments – 60 million car accidents happen each year, and more than 90 people a day die as a result of a car accident.

Are we doing this because we’re willfully deceitful assholes?

Well … maybe for some of you. (I can’t rule out the asshole exception entirely, sorry.)

But, for the most part, much like our biological programming to establish/retain a sense of tribal belonging flips our fear switches when we try to be nonconformist and stand out, we also naturally show tendencies toward …

I. WE ALMOST ALWAYS SHOOT THE MESSENGER

I want to circle back to a point I made earlier about myself. Yes, I don’t love being put on the spot with a question I don’t know how to answer.

However, the mental sinkhole that opens up in my stomach when I do know the answer, but it’s not an answer that will make anyone happy – e.g., there is no magical content wizard who will create your content for you, it does require some effort on your part – is one that makes me cringe.

And once again, science shows there’s a good reason why most of us feel that way.

Check out the absolutely bonkers research findings I came across in Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion (5th Edition):

"In a set of eleven studies, someone assigned to simply read aloud a piece of bad news became disliked by its recipients; interestingly, the reader was also seen as having malevolent motives and was rated as a less competent individual."

This has two broader implications for us as experts in our field:

First, I’m going to go out on a limb and say that while the above data is shockingly black-and-white, deep down we’re not really that surprised. We never want to be the bearers of bad news; we avoid tough conversations to the point where there are thousands of books and articles about how to have them.

So, in our content and on stages and in one-to-one prospect/client interactions, we shy away from the tough stuff. (And sometimes what someone doesn’t want to hear is, “I don’t know” or “There is no simple answer to what you’re asking me.”)

Related to this …

II. WE’RE ALSO CONFIRMATION BIAS JUNKIES

When bad news or negative new information comes to light, we’re more likely to try and dismiss it if it contradicts any of our steadfast (and publicly held) views.

This little graphic from Farnam Street sums this up nicely:

Like Leo Tolstoy once said, because I love relying on smarter people to make my points for me (dead or alive):

“The most difficult subjects can be explained to the most slow-witted man if he has not formed any idea of them already; but the simplest thing cannot be made clear to the most intelligent man if he is firmly persuaded that he knows already, without a shadow of doubt, what is laid before him.”

So it’s not terribly surprising that, as we climb up the thought leadership ladder (individually or as an organization), the more concerned we are with falling off.

And the higher we climb:

The more afraid we become because the costs of doing so increase as we ascend.

The less likely we are to be open-minded to new ideas; we become more cemented in our beliefs and become more dogmatic than educational in helping our target audiences solve their problems.

I’ve experienced this fear throughout my own career

I wish I could say I’ve been immune to lapsing into dogmatic behavior as a supposed expert in what I do, but I’d be flat-out lying to you. Unfortunately, there have been instances where I’ve acted hesitant (if not somewhat hostile) toward new ideas (strategies, processes, technologies) that seemingly threatened my publicly broadcasted expertise as a content strategy professional.

Yes, that’s an ugly thing to admit, and it’s true.

I’ve gotten better over the years at managing this reflex, but back in the good ol’ drama queen days, I’d quietly wallow in thought cycles like:

I’m afraid of looking foolish because I didn’t know something I should have.

I’m afraid others around me would believe I should have seen these things coming.

I’m afraid of being perceived as a dinosaur.

I’m afraid of blowback of having to say that getting results will take longer than expected due to the now needed pivots for the change I didn’t foresee and … oh my gosh, I look incompetent.

To be clear, I’m not implying we’re all spiraling out of control emotionally every time something knocks us off our game or contradicts an idea we preach as gospel to the masses. But let’s not kid ourselves; we all feel that little lurch in our stomach the moment we encounter a bit of new information we don’t like.

But our audiences don’t want us to be perfect all the time

Our futile pursuit of perfection boils down to one simple thing – we want our desired audiences to trust us … more specifically, we want them to trust us more than others.

That’s because trust is kind of a big deal in the world of marketing and thought leadership. Especially since 70% of consumers (regardless of age, gender or income) say brand trust is now more important than ever to their purchasing decisions.

How do we build trust? Well, I’ve been skimming articles about how to build trust as a business over the past week or so, and the most common pieces of advice I came across are:

Act with honesty and integrity

Deliver on your promises

Don’t hide when you make a mistake, have the tough conversations proactively

Don’t say one thing and do another

You know, the don’t-be-a-shitty human/organization starter pack.

Do you know what I didn’t find? I didn’t find a single article that said:

“You need to be a perfect know-it-all who only provides uncomplicated answers people want to hear if you want to build trust as a brand or thought leader.”

Quite frankly, if you’re a perfect know-it-all who acts like they know everything and only tells me stuff that makes me happy, I’m not going to trust you, and the right people won’t either. You’ll be the kind of person or brand that makes everyone slightly uncomfortable because perfection does not exist.

If you want to be a thought leader or a trusted brand in a particular space, you need to smash the reset button on how you view the promises you’re keeping to your audience:

You can publish something as an absolute one day and then correct yourself later on and say, "I was wrong; here’s how and why I was wrong, and here’s what I’ve learned.”

You're allowed to invite the people you're trying to reach alongside you in your journey of learning, where you achieve enlightenment and discovery together; you don’t already need to be at the top of the mountain, you can just be the exact someone who is finally asking the right questions and seeking those answers.

You can admit you don’t know something and then say, “I am now going to work tirelessly to figure out the answer and get back to you; for now, here is what I can tell you.”

You can say things out loud like, “Hey, you may not always love what I have to say, but you can trust what I say. I respect who you are and what you’re doing/working toward too much to sugarcoat something, or lie to you about what is or isn’t possible.”

You can and will still be taken seriously as an expert when you act like a human being.

And if someone penalizes you for being a human who is open to new ideas, doesn’t have every answer right at their fingertips, and is more focused on being honest than being likable … well, that says a lot more about them than it does about you.

Originally published for BS+Co.